The global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis, projected to cause 10 million annual deaths by 2050, has rendered entire classes of traditional antibiotics obsolete, creating a desperate and growing therapeutic void valued at over $40 billion. In this escalating battle, Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs)—nature’s ancient defense molecules—have emerged from scientific curiosity to the forefront of clinical innovation, with over 80 candidates now in various stages of development. Unlike conventional antibiotics, AMPs employ rapid, multi-mechanistic attacks on bacterial membranes, presenting a formidable barrier to resistance development. This comprehensive analysis examines the current clinical development status of synthetic and engineered AMPs, detailing the promising candidates in late-stage trials, dissecting the unique pharmacokinetic and manufacturing challenges, and mapping the strategic pathway for these next-generation agents to reach patients and redefine the standard of care for multidrug-resistant infections.

The AMR Crisis and the Imperative for Novel Mechanisms

The dwindling efficacy of existing antibiotics necessitates a paradigm shift in how we combat bacterial infections, creating a fertile ground for AMP development.

The Scale of the Multidrug-Resistance Challenge

Key pathogens driving the unmet medical need:

- ESKAPE Pathogens: Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species are the leading causes of nosocomial infections that evade treatment.

- Carbapenem-Resistant Organisms (CROs): Gram-negative bacteria producing carbapenemases represent a critical threat, with few to no reliable antibiotic options.

- Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus (MRSA): While new drugs exist, resistance and recurrence remain significant problems, particularly in complicated skin and soft tissue infections (cSSTIs).

Why AMPs Are a Strategically Compelling Solution

Inherent advantages over small-molecule antibiotics:

- Low Propensity for Resistance: Killing via membrane disruption or multiple intracellular targets is genetically complex for bacteria to counteract compared to single-enzyme inhibition.

- Broad-Spectrum Activity: Many AMPs are effective against a wide range of Gram-positive, Gram-negative bacteria, and even fungi.

- Anti-Biofilm Activity: A critical differentiator; many AMPs can penetrate and disrupt bacterial biofilms, which are responsible for chronic, device-related infections and highly resistant to antibiotics.

- Immunomodulatory Properties: Some AMPs can modulate the host immune response (e.g., by recruiting immune cells or neutralizing endotoxins), adding a therapeutic dimension.

“Antimicrobial peptides represent the first truly novel class of anti-infectives in decades. We are not just creating another molecule to inhibit a bacterial enzyme; we are deploying a fundamentally different strategy—physically targeting the integrity of the bacterial membrane itself. This is our best hope for outmaneuvering bacterial evolution in the long term.” — Dr. Lena Kowalski, Director of Infectious Disease Research, Global Health Institute.

Mechanisms of Action: The Multi-Faceted Attack

Understanding how AMPs kill bacteria is key to appreciating their clinical potential and design strategies.

Primary Mechanism: Membrane Disruption

The most common and rapid bactericidal action:

| Model | Description | Example AMPs |

|---|---|---|

| Barrel-Stave | Peptides insert into the membrane, aggregate, and form a pore, causing leakage. | Alamethicin |

| Carpet | Peptides cover the membrane surface like a carpet, eventually causing micellization and disintegration. | LL-37, Cecropin |

| Toroidal Pore | Peptides induce lipid monolayers to bend continuously, forming a pore lined by both peptide and lipid headgroups. | Magainin 2 |

Secondary and Intracellular Targets

Actions that occur after membrane interaction or independently:

- Inhibition of Macromolecule Synthesis: Binding to DNA, RNA, or protein synthesis machinery.

- Enzyme Inhibition: Targeting critical bacterial enzymes.

- Immunomodulation: Acting as chemoattractants for immune cells or modulating inflammatory cytokine responses.

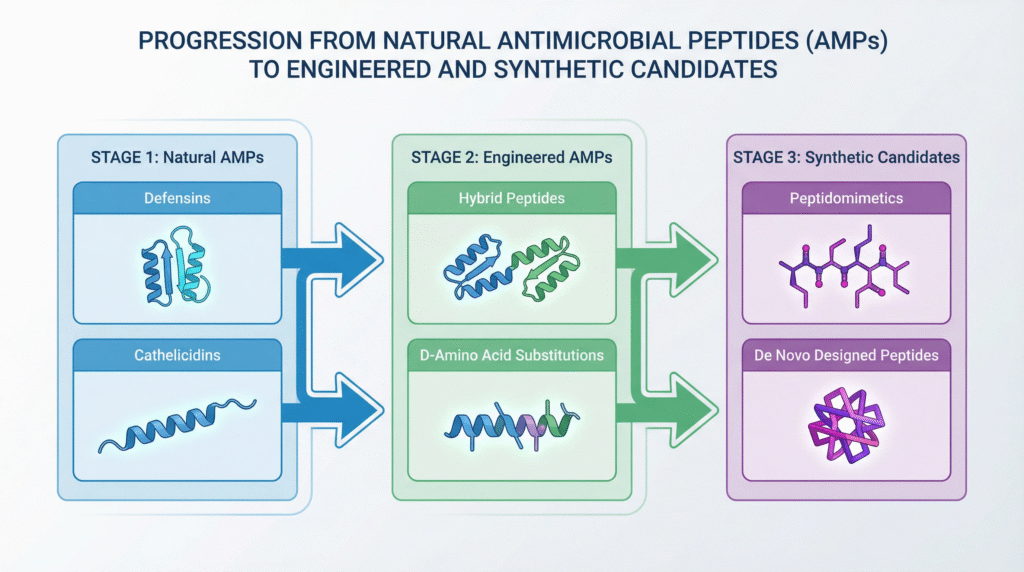

The Clinical Pipeline: From Natural to Engineered Candidates

The AMP development landscape is diverse, encompassing natural derivatives, synthetic analogs, and fully engineered peptides optimized for drug-like properties.

Late-Stage Clinical Candidates (Phase 2/3 and Approved)

Leading the charge towards commercialization:

| Candidate (Company) | Origin / Type | Indication (Phase) | Key Differentiator / Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Murepavadin (Polyphor) | Engineered peptidomimetic (Macrocycle) | Nosocomial Pneumonia caused by P. aeruginosa (Phase 3 completed) | Outer membrane protein target; development reportedly halted due to specific kidney toxicity, but remains a key pipeline proof-of-concept. |

| Surotomycin (Cubist/Merck) | Lipopeptide (Derivative of daptomycin) | C. difficile Infection (Phase 3) | Gut-restricted activity minimizes systemic exposure. Development status uncertain post-acquisition. |

| Novexatin® (NP213) (Novabiotics) | Synthetic cationic peptide | Fungal Nail Infection (Onychomycosis) (Phase 3) | Topical application; demonstrates biofilm penetration. |

| LTX-109 (Lytix Biopharma) | Synthetic antimicrobial peptidomimetic | Decolonization of MRSA (Phase 2) | Rapid, broad-spectrum topical agent. |

| Brilacidin (Innovation Pharmaceuticals) | Small-molecule defensin mimetic | Oral Mucositis, cSSTI (Phase 2) | Mimics host defense protein function; dual anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activity. |

Notable Approved AMPs and Their Lessons

First-generation successes that paved the way:

- Daptomycin (Cubicin®): A lipopeptide approved for cSSTI and S. aureus bacteremia. It functions by membrane depolarization. Its success proved the clinical viability of membrane-targeting agents but also highlighted potential toxicity (myopathy) requiring monitoring.

- Polymyxins (Colistin, Polymyxin B): Natural peptide antibiotics revived as last-resort treatments for Gram-negative infections. Their significant nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity underscore the critical importance of optimizing the therapeutic window in new AMP design.

- Gramicidin: A topical peptide used in ointments, demonstrating the historical utility and local application niche for AMPs.

Formulation and Delivery Challenges in AMP Development

Translatings promising in vitro activity into effective and safe drugs requires overcoming significant pharmaceutical hurdles.

Pharmacokinetic and Stability Hurdles

- Proteolytic Degradation: Rapid cleavage by serum and tissue proteases leads to short half-lives, limiting systemic use.

- Poor Oral Bioavailability: Susceptibility to gut proteases and poor membrane permeability generally restrict AMPs to IV or topical routes.

- Binding to Serum Proteins: Nonspecific binding can sequester the peptide, reducing free fraction available for antimicrobial activity.

- Renal Clearance: Small peptides are often rapidly cleared by the kidneys.

Innovative Solutions and Design Strategies

How developers are engineering around the limitations:

| Challenge | Engineering/Formulation Strategy | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Proteolysis | Use of D-amino acids, cyclization, peptidomimetic backbones. | Bacitracin (cyclic), Murepavadin (macrocycle). |

| Systemic Toxicity | Targeted delivery (liposomes, nanoparticles), prodrug strategies, optimizing charge/hydrophobicity balance. | Liposomal formulation of AMPs for reduced nephrotoxicity. |

| Short Half-life | PEGylation, fusion to albumin-binding domains, sustained-release depots. | PEGylated versions of LL-37 in development. |

| High Manufacturing Cost | Improved solid-phase synthesis, recombinant production in microbial systems, novel chemical ligation methods. | Recombinant production of longer AMPs in E. coli or yeast. |

Regulatory and Commercial Pathway for AMPs

Navigating approval and market access for a novel anti-infective class presents unique considerations.

Regulatory Considerations (FDA/EMA)

- Path to Approval: Typically follows the traditional antibiotic development pathway via non-inferiority trials. There is growing discussion about pathogen-specific, limited population pathways (e.g., LPAD in the U.S.) for drugs targeting highly resistant infections.

- Unique CMC Requirements: Peptide APIs require stringent control over sequence, purity, stereochemistry, and aggregation state. Demonstrating consistency in large-scale GMP manufacturing is critical.

- Safety Profile: Given the history of toxicity with some peptides (e.g., polymyxins), regulators will closely scrutinize renal, neurological, and hemolytic potential.

Market Access and Reimbursement

- Stewardship & Pricing: As potential last-line agents, their use will be heavily stewarded. This supports a premium pricing model but may limit volume. Value-based pricing linked to reduced mortality, length of hospital stay, and prevention of spread is key.

- Diagnostic Dependency: Optimal use requires rapid diagnostic tests to identify the resistant pathogen, creating a companion market need.

Future Directions and Next-Generation Platforms

The field is evolving beyond natural peptide mimics towards intelligent, multi-functional therapeutic platforms.

Advanced Engineering and Discovery Platforms

- AI/ML-Driven Design: Using machine learning to design novel peptide sequences with optimal activity, stability, and low toxicity profiles, exploring vast chemical spaces beyond natural templates.

- Combination Therapies: Developing AMPs that synergize with existing antibiotics to resurrect their efficacy or slow resistance development.

- Targeted AMPs: Conjugating AMPs to antibodies or other targeting moieties to direct them specifically to infection sites, minimizing off-target toxicity.

- Immuno-AMPs: Designing peptides where antimicrobial and immunomodulatory functions are explicitly engineered and balanced to clear infection and modulate damaging inflammation.

Alternative Applications Beyond Systemic Infection

Areas with high near-term potential:

- Medical Device Coatings: Impregnating catheters, implants, and wound dressings with AMPs to prevent biofilm formation and device-related infections.

- Agricultural and Veterinary Use: As alternatives to growth-promoter antibiotics in livestock, reducing the environmental pressure for AMR development.

- Topical Therapies: For diabetic foot ulcers, burn wound infections, and dermatological conditions where local delivery bypasses systemic PK challenges.

FAQs: Antimicrobial Peptide Clinical Development

Q: If AMPs are so promising and have been known for decades, why are there so few approved for systemic use compared to traditional antibiotics?

A: The historical slow progress is due to a confluence of significant technical and commercial challenges. Technically, early natural AMPs suffered from poor stability in the body (rapid degradation by proteases), toxicity to human cells (hemolysis, nephrotoxicity), and high manufacturing costs. Commercially, the antibiotic market has been challenging, with lower returns on investment compared to other therapeutic areas, discouraging high-risk development. Today, advances in peptide engineering (D-amino acids, cyclization), formulation science, and a dire clinical need due to AMR are finally overcoming these barriers, leading to the current wave of late-stage candidates.

Q: What is the biggest safety concern with systemically administered AMPs, and how is it being addressed?

A: The primary safety concern is nephrotoxicity (kidney damage), as seen historically with polymyxins. This is often linked to the cationic nature of AMPs, which can cause accumulation and disruption of renal tubular cells. Developers address this through sophisticated design: optimizing the peptide’s net charge and hydrophobicity balance to maintain antimicrobial activity while reducing host cell toxicity. New candidates undergo rigorous preclinical renal safety assessments. Formulation strategies, like packaging AMPs in liposomes that release drug at the infection site, are also explored to minimize systemic kidney exposure.

Q: For a bacterial infection, would an AMP be used as a first-line treatment or strictly as a last resort?

A: The intended use depends on the specific AMP’s spectrum, safety profile, and development pathway. Most in late-stage development for serious resistant infections (e.g., VABP, cSSTI) are initially targeted as last-resort or second-line therapies for pathogens resistant to first-line antibiotics, aligning with stewardship principles. However, topical AMPs (e.g., for skin or eye infections) could be first-line. In the future, if an AMP demonstrates an exceptional safety profile and a very high barrier to resistance, it could potentially be considered for broader first-line use, especially in hospital settings to prevent the spread of resistant strains. The initial strategy is to establish efficacy in the highest-need populations.

Core Takeaways

- Urgent Solution for AMR: AMPs represent one of the most promising novel therapeutic classes to address the global antimicrobial resistance crisis, employing mechanisms that make resistance development significantly harder for bacteria.

- Diverse and Advancing Pipeline: Over 80 candidates are in development, with several in Phase 2/3 trials for indications ranging from complicated skin infections to pneumonia, demonstrating tangible progress towards the clinic.

- Engineering Overcomes Hurdles: Historical challenges of stability, toxicity, and cost are being addressed through advanced peptide engineering (D-amino acids, cyclization), novel formulations, and improved manufacturing processes.

- Beyond Direct Killing: The potential of AMPs extends beyond bactericidal activity to include anti-biofilm and immunomodulatory functions, offering a multi-pronged therapeutic approach.

- Strategic Development Pathway: Successful translation requires navigating unique CMC, regulatory, and market access landscapes, with an initial focus on high-unmet-need, resistant infections where the value proposition is strongest.

Conclusion: A New Frontier in the Fight Against Superbugs

The clinical development of Antimicrobial Peptides marks a pivotal turning point in the human struggle against multidrug-resistant infections. Moving from natural inspirations to engineered therapeutic agents, AMPs are poised to transition from promising concept to practical reality within the next decade. The convergence of advanced biotechnology, a refined understanding of peptide design, and an undeniable public health imperative has created the necessary conditions for this class to finally deliver on its long-held potential.

The path forward requires sustained collaboration between researchers, clinicians, regulators, and payers to optimize these agents, ensure their appropriate use, and integrate them into effective antimicrobial stewardship programs. While challenges remain, the progress in the clinical pipeline is undeniable. AMPs are no longer just molecules of scientific interest; they are emerging as essential weapons in the medical arsenal, offering a robust and innovative strategy to safeguard modern medicine against the rising tide of bacterial resistance.

Disclaimer

This article contains information, data, and references that have been sourced from various publicly available resources on the internet. The purpose of this article is to provide educational and informational content. All trademarks, registered trademarks, product names, company names, or logos mentioned within this article are the property of their respective owners. The use of these names and logos is for identification purposes only and does not imply any endorsement or affiliation with the original holders of such marks. The author and publisher have made every effort to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided. However, no warranty or guarantee is given that the information is correct, complete, or up-to-date. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of any third-party sources cited.