The global peptide Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) manufacturing landscape is dominated by multi-product facilities (MPFs), where agility and cost-efficiency are paramount. However, this shared equipment model introduces a critical and non-negotiable risk: cross-contamination. For peptide therapeutics, where impurity profiles are complex and biological activity can be potent at trace levels, the consequences of inadequate cleaning—a patient receiving a mixture of APIs or harmful degradants—are catastrophic. Regulatory authorities mandate a science- and risk-based approach to cleaning validation, with a particular focus on demonstrating control over impurity carryover. This article provides a comprehensive, actionable guide to designing and executing peptide impurity carryover studies that are fully compliant with ICH Q3 guidelines.

We will explore advanced risk assessment methodologies, scientifically justified acceptance limits, state-of-the-art analytical strategies for trace-level detection, and robust protocols for multi-product facilities, empowering manufacturers to guarantee patient safety and uphold the strictest standards of quality and compliance.

The High-Stakes Challenge of Multi-Product Peptide Manufacturing

Manufacturing multiple peptide APIs in shared equipment maximizes asset utilization but creates a complex web of contamination risks that must be proactively managed.

Unique Risks of Peptide Cross-Contamination

Peptides present distinct challenges that heighten the risk and impact of carryover:

- High Potency and Biological Activity: Many therapeutic peptides are active at microgram or even nanogram doses. Minute levels of carryover from a highly potent peptide could elicit a pharmacological or immunogenic response in a patient.

- Complex and Sticky Impurity Profiles: Peptide synthesis generates a milieu of related substances (deletion sequences, truncated peptides, diastereomers, aggregates) that can vary significantly in solubility and adhesion properties, making them difficult to remove.

- Adsorption to Surfaces: Peptides can strongly adsorb to stainless steel, glass, and polymer surfaces used in reactors, tubing, and chromatography columns, resisting standard cleaning protocols.

- Diverse Chemical Properties: A facility may synthesize highly hydrophobic peptides, cationic antimicrobial peptides, and large, hydrophilic peptides sequentially. A cleaning procedure effective for one may be inadequate for another.

The Regulatory Imperative: ICH Q7 and Health Authority Expectations

The foundation for cleaning validation is unequivocal. ICH Q7, “Good Manufacturing Practice Guide for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients,” states:

- Paragraph 12.7: “Cleaning procedures should be validated… The rationale for the selection of cleaning agents and methods should be documented.”

- Paragraph 12.71: “Validation should consider the removal of previous product, removal of residual cleaning agents, and the removal of degradants.”

- Health authorities (FDA, EMA) expect a risk-based approach. The focus has shifted from arbitrary “visually clean” standards to demonstrating that carried-over impurities are reduced to a scientifically justified safe level.

“In a multi-product peptide facility, your cleaning validation is your primary defense against a quality catastrophe. It’s not about proving the equipment looks clean; it’s about providing irrefutable scientific data that the next product in line is free from harmful contamination. The carryover study is the experiment that provides that proof.” — Dr. Anya Sharma, Head of Quality Systems, Global CMO Network.

Foundations: Establishing Scientifically Justified Acceptance Limits

The cornerstone of a compliant carryover study is the calculation of a Maximum Allowable Carryover (MAC) limit. This defines the “safe” threshold.

The Health-Based Exposure Assessment (HBEA) Approach

Modern, ICH-aligned practice moves away from the outdated 10 ppm or 1/1000 of dose criteria. The HBEA determines a Permitted Daily Exposure (PDE) or Acceptable Daily Exposure (ADE).

- Identify the “Worst-Case” Previous Product: Select the API (or its most toxic significant impurity) that is most hazardous (lowest PDE) and hardest to clean from the equipment train.

- Calculate the PDE/ADE: Using toxicological data (NOAEL, LOAEL) from preclinical studies, apply appropriate assessment factors to derive a dose (in mg/day) that is deemed safe for a patient to ingest daily without adverse effect.

- Calculate the MAC for Equipment Surfaces:

- MAC (mg) = (PDE of Previous API) x (Minimum Batch Size of Next Product) / (Maximum Daily Dose of Next Product)

- This calculates the total allowable mass of the previous API that could be present in an entire batch of the next product.

- Calculate the Concentration-Based Acceptance Limit:

- Distribute the total MAC across the worst-case shared equipment surface area and the volume of the cleaning rinse/solvent or swab sampling solution.

- This yields a concentration limit (e.g., µg/mL, ng/cm²) that becomes the target for analytical method sensitivity and the pass/fail criterion for the study.

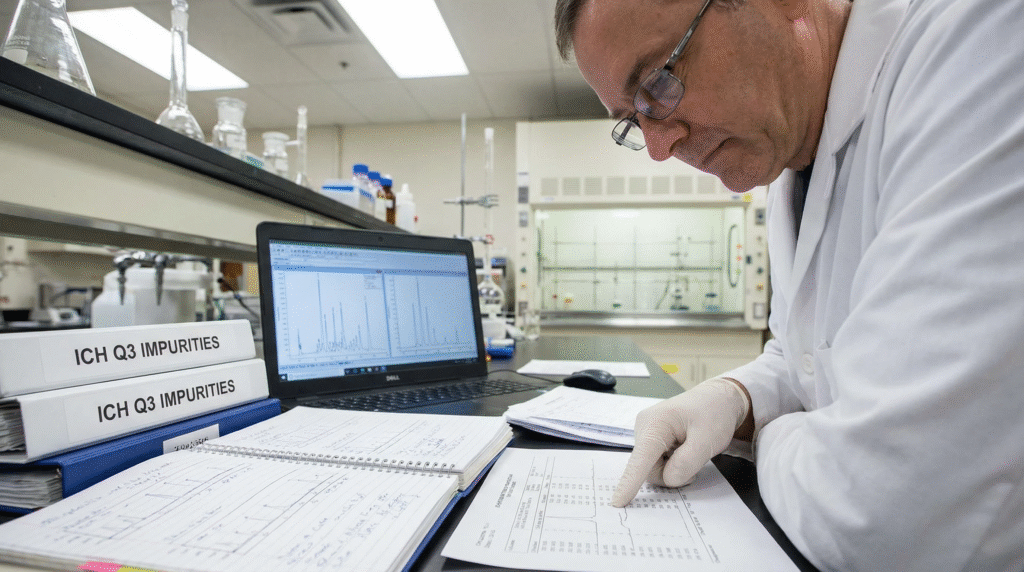

Special Considerations for Peptide Impurities

For peptides, the “previous product” may not be the API itself, but a critical impurity:

- Genotoxic Impurities: If the previous peptide synthesis uses reagents or generates impurities with structural alerts per ICH M7, the carryover limit must be based on the much stricter Threshold of Toxicological Concern (TTC) for that mutagenic impurity (e.g., 1.5 µg/day).

- Highly Potent or Hormonal Peptides: These will have very low PDEs, resulting in extremely stringent (parts-per-billion or trillion) MACs, pushing analytical capabilities to their limit.

Designing and Executing the Impurity Carryover Study

With limits defined, the study must be meticulously designed to simulate worst-case conditions and generate defensible data.

Risk Assessment and Study Scope Definition

A science-based risk assessment determines what to study:

| Risk Factor | Assessment Question | Outcome for Study Design |

|---|---|---|

| Product Potency & Toxicity (Danger) | Which product/impurity has the lowest PDE? | Defines the “marker” compound for the study. |

| Solubility & Cleanability (Difficulty) | Which product is least soluble in the cleaning agents? | Defines the “worst-case” previous product for cleaning challenge. |

| Equipment Design & Process (Contact) | Which equipment areas are hardest to clean (e.g., dead legs, filters, product contact hoses)? | Defines worst-case sampling locations. |

The Three-Batch Protocol and Worst-Case Conditions

Regulators expect a minimum of three consecutive successful cleaning cycles to demonstrate reproducibility.

- Manufacture the “Dirtiest” Batch: The previous product batch should be manufactured under standard conditions. No artificial soiling is typically required or recommended for peptides.

- Execute the Cleaning Procedure: Perform the routine cleaning procedure exactly as written, but under “challenge” conditions: at the longest allowed hold time before cleaning, using the minimum stated cleaning agent concentration, temperature, and flow rate.

- Sample Using Rinse and Swab Methods:

- Rinse Sampling: Collect the final rinse water/solvent from the entire system. Good for soluble residues and large, inaccessible areas.

- Swab Sampling: Physically swab predetermined worst-case locations (e.g., behind mixer blades, gasket seats) using validated swabs and solvent. Essential for demonstrating removal of adsorbed or insoluble residues.

- Analyze Samples: Analyze all samples using a validated, stability-indicating analytical method with sensitivity at least 10-50% of the calculated MAC limit.

- Repeat for Two More Cycles: Demonstrate consistent cleaning performance over three successive batches.

Advanced Analytical Strategies for Trace-Level Peptide Detection

Meeting the low MACs for peptides requires moving beyond standard HPLC-UV.

Method Selection and Validation

| Analytical Challenge | Recommended Technique | Key Validation Parameters for Carryover |

|---|---|---|

| Detection of Specific Peptide API or Related Substance | Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Specificity, LOD/LOQ (must be below MAC), precision, recovery from swabs/surfaces. |

| Broad Screening for Unknown Peptide Residues | High-Resolution LC-MS (Q-TOF, Orbitrap) with peptide mapping | Ability to detect and identify unexpected peptides from degradation or sequence variants. |

| Total Organic Carbon (TOC) as a Nonspecific Screen | TOC Analyzer | Recovery, specificity (must demonstrate the cleaning agent and product contribute similarly to TOC). Limited for peptides as it cannot identify the source. |

Overcoming Matrix Interference and Recovery Challenges

- Swab Recovery Studies: Must be performed by spiking a known amount of the marker peptide onto a coupon of the equipment surface material (e.g., 316L stainless steel), allowing it to dry, then swabbing and extracting. Recovery should be >70-80%.

- Cleaning Agent Interference: The analytical method must be able to separate and quantify the peptide residue in the presence of the cleaning agent (e.g., detergents, acids, bases) at its residual concentration.

Lifecycle Management: Cleaning Verification and Continuous Monitoring

Validation is not a one-time event. A robust program ensures ongoing control.

Cleaning Verification vs. Validation

- Validation: The initial, extensive three-batch study that establishes the scientific basis that the procedure works.

- Verification: The routine, post-cleaning testing performed after each manufacturing campaign in a multi-product facility. It uses a subset of the validated test (often just rinse TOC or a specific LC-MS/MS test) to confirm the cleaning was effective for that specific product changeover.

Managing a Matrix of Products and Procedures

In a large MPF, validating every product-to-product sequence is impractical. A “matrix” or “bracketing” approach is used:

- Grouping by Cleanability: Group products with similar physical-chemical properties (solubility, potency) and use a single worst-case validation for the group.

- Worst-Case Validation: Validate the cleaning procedure for the most challenging combination (most toxic, least soluble product cleaned to the most sensitive next product). This validation can then be leveraged for less risky sequences with scientific justification.

Future Trends: Automation, Modeling, and Advanced Detection

The field of cleaning validation is becoming more predictive and efficient.

- Cleaning Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Use of inline sensors (conductivity, UV, FTIR) to monitor cleaning solution composition in real-time, enabling endpoint detection and moving from fixed-time to condition-based cleaning.

- Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Modeling: To predict cleaning agent flow and shear forces in complex equipment, identifying dead zones that require focused sampling.

- Environmental Monitoring (EM) for Airborne Cross-Contamination: For highly potent peptides, monitoring the manufacturing suite air for API particles becomes an additional layer of control.

FAQs: Peptide Impurity Carryover Studies

Q: For a new peptide API facility, at what stage in development should we perform our first cleaning validation?

A: The timing is phase-appropriate. For clinical Phase I and II, a robust cleaning verification program with scientific justification is typically sufficient, as product volumes are low and the patient population is limited. However, the cleaning procedures and analytical methods should be developed early. Full cleaning validation is required prior to the manufacture of pivotal Phase III clinical trial material that will support a marketing application. This ensures the commercial manufacturing process, including changeover, is locked in and the data is available for pre-approval inspections.

Q: Can we use Total Organic Carbon (TOC) analysis for peptide cleaning validation, or is LC-MS/MS always required?

A: TOC can be used as a nonspecific test, but with significant caveats for peptides. It is excellent for detecting residual cleaning agents and general organic soil. However, it cannot distinguish between a harmless sugar excipient and a potent peptide API. Its use for peptide API carryover is only defensible if you can scientifically prove that: 1) The peptide is the major source of carbon in the residue, and 2) The calculated MAC limit, when converted to a carbon equivalent, is above the LOQ of the TOC method.

For most potent peptides with low MACs, LC-MS/MS is the necessary, specific technique. A common strategy is to use TOC for routine verification and specific LC-MS/MS for validation and periodic verification.

Q: How do we handle cleaning validation when our peptide is manufactured by a Contract Development and Manufacturing Organization (CDMO)?

A: Responsibility is shared but defined. The CDMO (e.g., Sichuan Pengting Technology Co., Ltd.) is responsible for executing and documenting the cleaning validation studies for their equipment and procedures. They should provide you with the validation protocols, reports, and scientific rationale. The sponsor (drug applicant) is responsible for auditing the CDMO’s cleaning validation program, providing toxicological data (PDE) for their product, and ensuring the overall approach is acceptable for their regulatory submissions. A strong Quality Agreement must explicitly define these roles. Choosing a CDMO with a transparent, science-driven cleaning validation program is critical for your regulatory success.

Core Takeaways

- HBEA is the Gold Standard: Acceptance limits for carryover must be based on a Health-Based Exposure Assessment (PDE/ADE), not arbitrary standards, aligning with ICH Q3 and Q9 principles.

- Risk-Based Design is Mandatory: Carryover studies must focus on worst-case scenarios: the most toxic/poorest solubility previous product, the hardest-to-clean equipment, and the most sensitive next product.

- Analytical Science is the Limiting Factor: Success depends on specific, highly sensitive methods (typically LC-MS/MS) validated for detection at levels significantly below the calculated MAC, including recovery from surfaces.

- Three is the Magic Number: A minimum of three consecutive successful cleaning cycles is required to demonstrate procedure reproducibility and robustness.

- Lifecycle Management is Continuous: Cleaning validation is not a one-time project. It requires ongoing verification, change control when processes or products change, and periodic re-validation.

Conclusion: Building Unshakeable Confidence in Multi-Product Operations

Executing rigorous, ICH Q3-compliant impurity carryover studies is a fundamental requirement for operating a credible and compliant multi-product peptide API facility. It is a direct demonstration of a company’s commitment to patient safety and quality. By adopting a modern, science- and risk-based framework—from calculating health-based limits to employing advanced detection technologies—manufacturers can transform cleaning validation from a compliance burden into a strategic asset that ensures supply chain flexibility, protects product integrity, and builds unwavering trust with regulators and partners.

The complexity of this undertaking highlights the value of expertise and robust systems. Success depends not just on protocol, but on the deep technical understanding of peptide chemistry, toxicology, and analytical science applied to real-world equipment. Sichuan Pengting Technology Co., Ltd. integrates this expertise into its core operations. As a professional and reliable peptide API supplier operating a multi-product facility, we have established a rigorous, defensible cleaning validation program. Our approach is built on scientifically justified HBEAs, worst-case study designs, and state-of-the-art LC-MS/MS analysis, ensuring cross-contamination risks are eliminated.

We provide our clients with transparent access to validation reports and data, offering them confidence that their valuable peptide API is manufactured in an environment where quality and patient safety are unequivocally prioritized. Partnering with a supplier that masters these complexities is a critical step in de-risking your peptide development and manufacturing journey.

Disclaimer

This article contains information, data, and references that have been sourced from various publicly available resources on the internet. The purpose of this article is to provide educational and informational content. All trademarks, registered trademarks, product names, company names, or logos mentioned within this article are the property of their respective owners. The use of these names and logos is for identification purposes only and does not imply any endorsement or affiliation with the original holders of such marks. The author and publisher have made every effort to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided.

However, no warranty or guarantee is given that the information is correct, complete, or up-to-date. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of any third-party sources cited.